By Rochele Padiachy and Usman Qazi

2025 marks the 10-year anniversary of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) final report and its Calls to Action. These 94 calls to action speak on a variety of issues where reconciliation advancements are needed, and 10 years later, there is still much work to be done. At the same time, we are witnessing a rapid technological transformation in artificial intelligence (AI), a powerful tool that is reshaping how we access, produce, and interact with information online.

Beyond ChatGPT: Understanding AI’s impact on inclusion

AI is trained in large-language models (LLMs) which are advanced systems that can perform cognitive functions such as learning and problem-solving, can create high quality content such as audio, images, text, and code.[1] An example that you have probably seen is ChatGPT, one of the better-known LLMs that can generate human-like text and photos in a conversational way. While there can be positive uses for an AI system such as ChatGPT, it also has high tendencies of providing incorrect information, potential negative biases from its training data, privacy concerns, and significant environmental impact from its energy use.[2]

This is important for people to consider because when we talk about AI and its intersection with DEIA, we should understand what it brings to these kinds of spaces. This technological boom has people wondering how it would affect and even influence inclusion, accessibility, and diversity frameworks. We need to think about DEIA values within the AI ecosystem, because without doing so, we risk reinforcing barriers to accessibility and awareness. One of these risks includes repeating harmful rhetoric that continue to harm Indigenous communities specifically. As AI becomes deeply embedded in our institutions, and as we think about the work that still needs to be done for the TRC and its Calls to Action, we must ask ourselves: what does it mean for Indigenous sovereignty in the digital age?

This is where techquity comes into play.

Techquity: Beyond access to agency

When we talk about techquity (technology + equity), we’re referencing something far deeper than access to Wi-Fi or a new device.[3] Techquity is focused on ensuring that the development of technology actively promotes equity and social justice for all communities. True equity in technology is about participation, the ability to help shape, govern, and benefit from the systems that increasingly define how we live and learn, and, more importantly, our connection to one another.[4]

Access without agency isn’t equity, it’s dependency guised as inclusion.

For many marginalized and racialized communities, even being connected hasn’t always meant being empowered. This holds true for many Indigenous communities across Canada and beyond. In a report written by The Assembly of First Nations and Indigenous Services Canada, the digital connectivity gap is severe, as only about 40% of First Nations communities have access to high-speed internet, while large existing disparities such as education, health, and employment continue to occur.[5] With the addition of AI, these spaces, without proper dialogue or consent, risk repeating old patterns and widen the digital connectivity gap. Innovation becomes another form of extraction rather than collaboration.

Without proper dialogue or consent, the addition of AI to these spaces risks repeating old patterns and widening the digital connectivity gap, where innovation becomes another form of extraction rather than collaboration.

Māori-led AI design: The koru model

So, the question isn’t just how Indigenous communities access AI, but who decides how it’s built, trained, and used. These tools should be developed in partnership with Indigenous communities, grounded in Indigenous worldviews and governance practices.

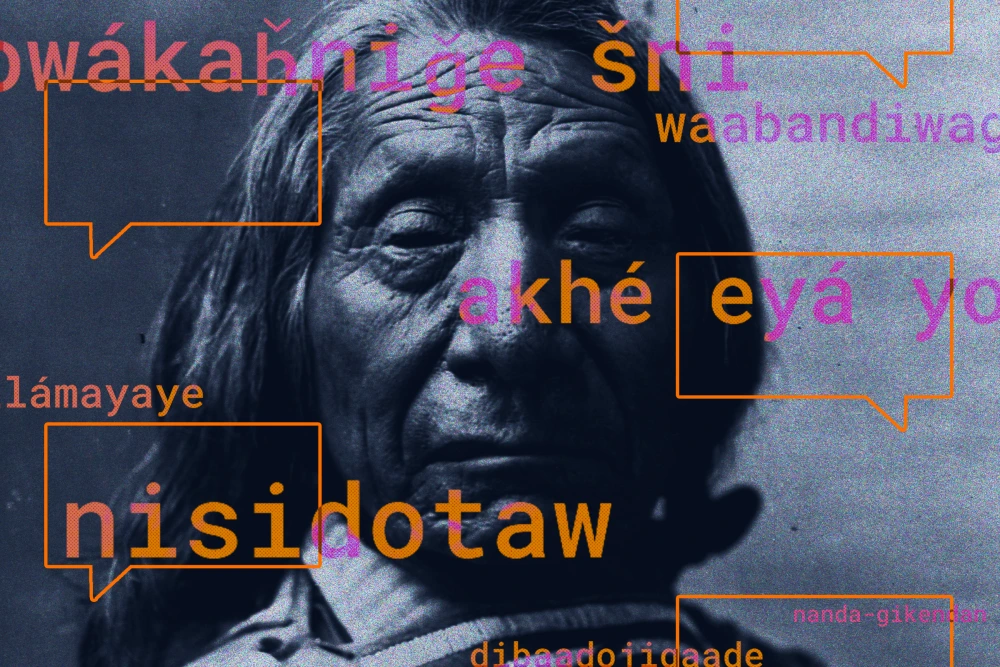

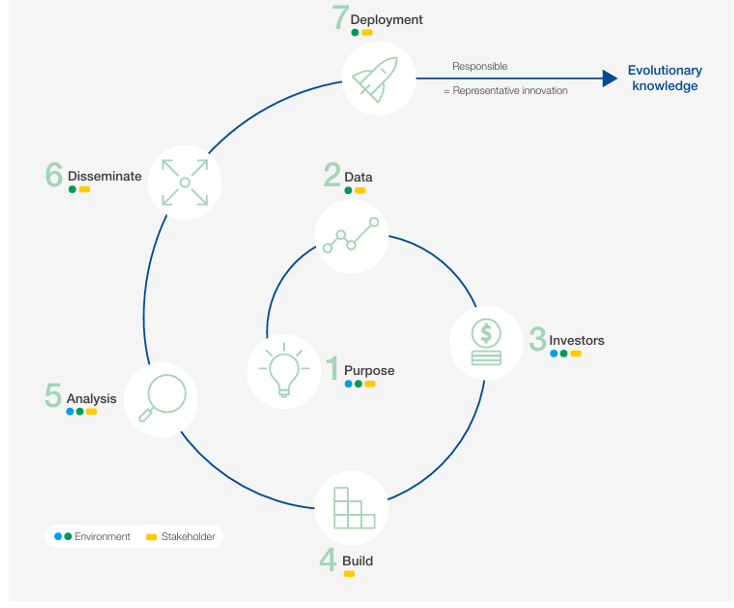

Around the world, Indigenous communities are already reframing this relationship. A powerful example of Indigenous leadership in AI comes from the work highlighted by the World Economic Forums Blueprint for Equity and Inclusion in Artificial Intelligence Published in 2022. The report draws on concepts developed by Sarah Cole Stratton of the Māori Lab, whose Māori-informed framework reframes the AI life cycle through Whakapapa (interconnection), Whanaungatanga (relational responsibility), and Kaitiakitanga (guardianship). Stratton was a one of the lead contributors to the WEC blueprint, where her Representative, Responsible, Evolutionary AI Life Cycle was spotlighted. Unlike conventional AI lifecycles that spin in closed loops of bias and repetition, Stratton’s model unfolds like a koru, the unfurling Punga fern symbolizing growth, renewal, and continuity [6].

This Māori-led framing offers a powerful alternative: an AI lifecycle that flows, unfolds, and adapts with each iteration, guided by community knowledge, environmental stewardship and shared governance. This reenvisioned lifecycle reflects broader truth, meaningful innovation is relational, iterative, and accountable, and it grows the way the koru does, always reaching toward responsible expansion.

The Māori Lab “koru” (Sara Cole Stratton)[7]

Data sovereignty: OCAP and the CARE principles

This is where the principle of Indigenous data sovereignty becomes relevant and essential. It is the fundamental rights[8] and regional frameworks seen in the OCAP (Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession) principles in Canada. [9]

An article written by the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), a global human rights organization dedicated to promoting and defending Indigenous Peoples’ rights, mentions[10] that Indigenous Peoples must be the decision-makers around how their data and cultural representations are used in digital systems.[11] In many cases, data collected from Indigenous and marginalized communities are extracted, commodified, and used without consent. Frameworks like the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance (collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, and ethics)12 remind us that data sovereignty is not just a technical standard, it’s a matter of respect, and self-determination.[12]

AI obscures this landscape further. AI systems engage massive data sets, most of which are untraceable in origin and often reflect historical and systemic bias. When these models are trained on unexamined data, they stand a very reasonable risk of multiplying and mirroring inequality. Without Indigenous participation and oversight, many have raised concerns that AI has the potential to become what some scholars refer to as data colonialism: the monetization and extraction of language, culture, and knowledge without consent or accountability.[13]

Indigenous AI in action: Examples from Latin America

Bridging the digital divide requires structural reforms, such as ethical data practices that respect community consent and autonomy and policies that support inclusive participation and cultural preservation.[14] Some countries have already begun experimenting with Indigenous-led AI initiatives that prioritize cultural preservation and community-led governance.

For example, a report titled Indigenous People-Centered Artificial Intelligence: Perspectives from Latin America and the Caribbean[15] emphasizes the importance of participatory inclusion, ethical data use, and AI systems rooted in Indigenous knowledge systems.[16] The digitization of Indigenous data must guarantee their right to self-determination and to govern their data, to use them under their values and common interests, the free, prior and informed consent for their collaborative participation, and to ensure their privacy and intellectual property rights”.[17] Some of the examples that include these protocols include:

- Researchers from the Technological Institute of Oaxaca created an AI-driven app that supported Tu’un Savi language revitalization, offering pronunciation and writing guidance using mobile phone cameras.[18]

- Researchers in Veracruz used natural language processing to evaluate pronunciation in Indigenous languages, supporting educational access.[19]

These examples highlight using DEIA values in the container of AI in an inclusive way.

Reconciliation in the digital age: Canada’s path forward

While we have been speaking about the AI ethics globally, the conversation about AI in the Canadian context must expand to include Indigenous data governance, and Indigenous sovereignty must be grounded in the TRC’s Calls to Action and the broader context of reconciliation. The conversation between AI and DEIA must be had with DEIA values in mind, and these values include living/lived experience, equity, and critical approaches, which are important when discussing the intersection of AI and DEIA in relation to supporting racialized and marginalized communities. Without intentional design, inclusive policy, and Indigenous leadership, AI risks becoming another tool of assimilation and exclusion.

With the advent of this new and rapidly emerging technology, as well as the issues that have been brought up globally by the UN and UNESCO, we are forced to critically examine where it leaves us. As we think about the TRC and the Calls to Action, we should ask ourselves whether AI perpetuates the same discriminations for Indigenous Peoples as before. Over the past 10 years, we have been shown that reconciliation is not static; it must evolve in conjunction with shifting social, political, and technological circumstances. And, in the present moment of rapid AI innovation, reconciliation must also contend with the frontier of digital sovereignty and techquity.

So, when we think about how Indigenous communities are affected by AI and its potential of mirroring harmful and historical patterns of dispossession, it can be scary when there is no control or guidelines that can mitigate these risks of digital exploitation and reinforcement of biases. Techquity allows for AI to be utilized in a container, and thinking about DEIA values, ensures human-centered approaches that can protect Indigenous People’s rights, empowering them as decision-makers and, if they choose to participate, allowing them to engage with the technology on their terms.[20] This approach lays the groundwork for an inclusive AI future, one in which Indigenous communities continue to shape the technologies in ways that honor their knowledge, autonomy, and rights.